By Michelle Maloney, PhD, Australian Earth Laws Alliance, Griffith Journal of Law & Human Dignity Vol 3 (1) 2015, Griffth University, Queensland, Australia

FINALLY BEING HEARD ~ VOL 3(1) 2015

CONTENTS

- I INTRODUCTION

- II EARTH JURISPRUDENCE: “WILD LAW” AND THE RIGHTS OF NATURE

- III THE GLOBAL ALLIANCE AND ITS CREATION OF THE RIGHTS OF NATURE TRIBUNAL

- IV THE GREAT BARRIER REEF CASE

- V REGIONAL CHAMBER: AUSTRALIA’S FIRST RIGHTS OF NATURE TRIBUNAL HEARS EVIDENCE ABOUT THE GREAT BARRIER REEF

- VI WHAT DOES THE INTERNATIONAL RIGHTS OF NATURE TRIBUNAL OFFER THE GREAT BARRIER REEF AND EARTH JURISPRUDENCE?

- VII CONCLUSIONS

I INTRODUCTION

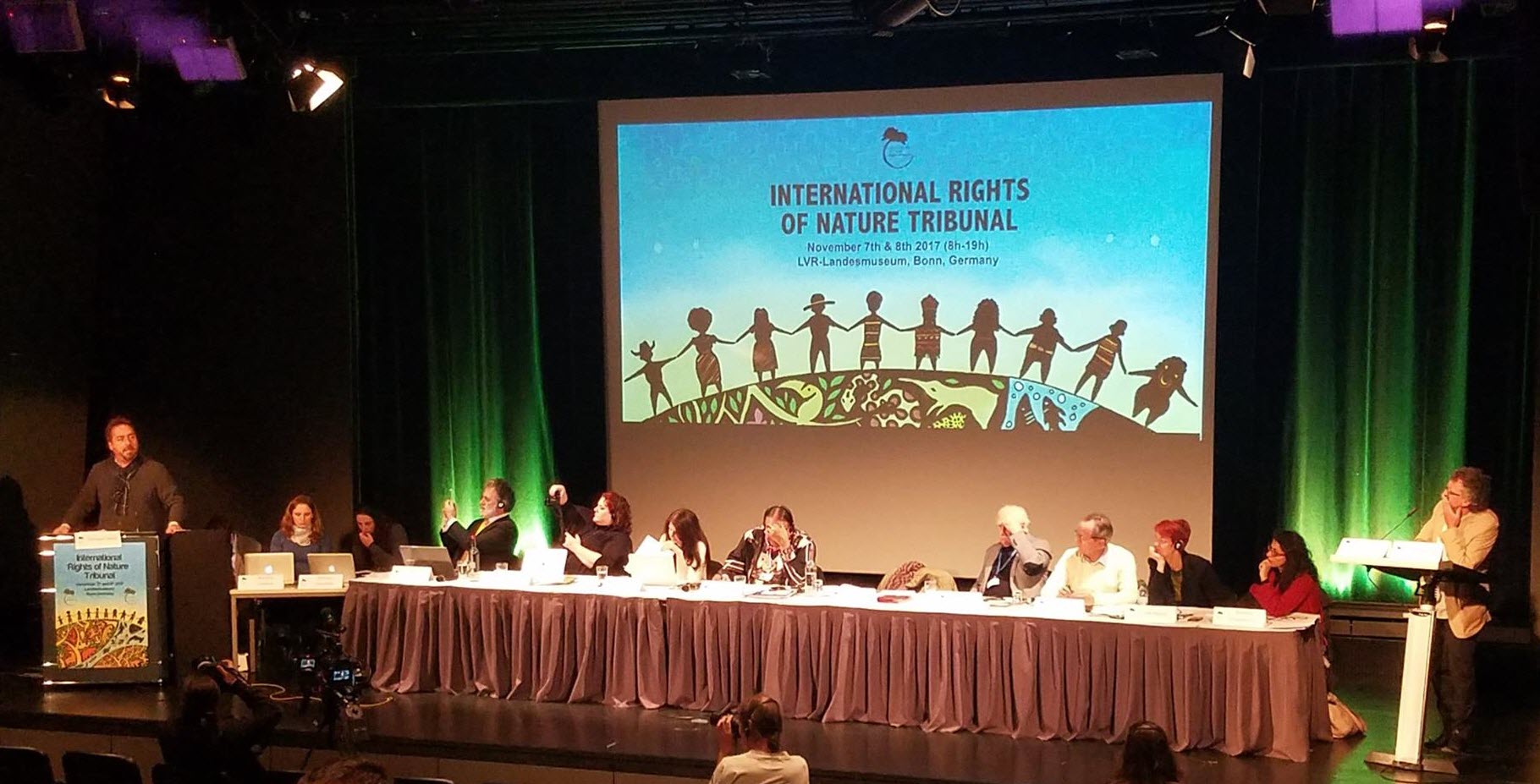

The International Tribunal for the Rights of Nature and Mother Earth (‘the Tribunal’) sat for the first time on 17 January 2014 in Quito, Ecuador. Created by international civil society network, the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, the Tribunal is comprised of lawyers and ethical leaders from indigenous and non-indigenous communities around the world.1 The objective of the Tribunal is to hear cases regarding alleged violations of the rights of nature and make recommendations about appropriate remedies and restoration.

The Tribunal’s main source of law is the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth (‘UDRME’).2 For cases brought about matters in Ecuador and Bolivia, the Tribunal can refer to the Ecuadorian Constitution and Bolivia’s Framework Act for the Rights of Mother Earth and Holistic Development to Live Well respectively, as these existing domestic legal instruments explicitly recognise the rights of nature.3

The UDRME was drafted at the World People’s Congress on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth, held in Cochabamba, Bolivia in 2010. It has been estimated that 30 000 people from more than 100 countries attended the gathering and played a part in drafting the UDRME.4 The UDRME is not presently recognised in formal international law but it represents the agreed values of thousands upon thousands of members of civil society. The UDRME was submitted to the UN shortly after the meeting in Cochabamba and was formally considered at the April 2011 UN Dialogue on Harmony with Nature. It featured prominently at the June 2012 UN Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20) and the Final Declaration of the Rio+20 People’s Summit called on ‘governments and people of the world to adopt and implement the UDRME’.5 While the final UN consensus document did not reference the UDRME, it did refer to the recognition of ‘rights of nature’ in the governing system of some of its member states.6

At a time when many jurisdictions are seeing their state-sanctioned environmental laws weakened or repealed,7 the Rights of Nature Tribunal is an important forum, both for drawing attention to an international audience about environmental atrocities and for reclaiming any notion of “justice” for these state sanctioned violations of the rights of nature. But in practical terms, what use is such a Tribunal when neither current International Law nor the legal systems of industrialised nations such as Australia, actually recognise the rights of nature? In this paper, I define Earth jurisprudence and the Rights of Nature and situate the International Rights of Nature Tribunal within the work of the Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature and the broader context of the ecological crisis. I then outline the Great Barrier Reef case, which the Australian Earth Laws Alliance (‘AELA’) took to the International Tribunal in Quito and progressed in October 2014, by convening a Regional Chamber of the International Tribunal in Australia.8

I argue that like many “people’s tribunals” before it, the Rights of Nature Tribunal offers a powerful alternative narrative to that currently offered by the mainstream legal system regarding environmental destruction. It is also pregnant with the promise of transforming existing law and offers a welcome, cathartic contribution to the burgeoning field of Earth jurisprudence.

II EARTH JURISPRUDENCE: “WILD LAW” AND THE RIGHTS OF NATURE

Earth jurisprudence, a term coined by cultural historian and “Earth scholar” Thomas Berry, is an emerging theory of Earth-centred law and governance.9 Advocates for Earth jurisprudence propose that the primary cause of the ecological crisis is anthropocentrism — a belief by people in the industrialised world that we are somehow separate from, and more important than, the rest of the natural world. Berry argues that this anthropocentric world view underpins all the governance structures of contemporary industrial society — economics, education, religion, law — and has fostered the belief that the natural world is merely a collection of objects for human use.10 In contrast, Earth jurisprudence suggests a radical rethinking of humanity’s place in the world, to acknowledge the history and origins of the Universe as a guide and inspiration to humanity and to see our place as one of many interconnected members of the Earth community.11 By ‘Earth community’ Berry refers to all human and ‘other than human’ life forms and components of the planet — animals, plants, rivers, mountains, rocks, the atmosphere — our entire Earth.12 Berry and the broader Earth jurisprudence movement acknowledge the inspiration and guidance that indigenous cultures and indigenous wisdom can provide to industrialised societies and the development of Earth jurisprudence. He suggests that ‘our great work’ is to transform human governance systems to create a harmonious and nurturing presence on the Earth.13

Responding to Berry’s work, Cormac Cullinan’s Wild Law: A Manifesto for Earth Justice was a direct call to shift our legal and governance systems to support the Earth community.14 Wild Laws are laws that express principles of Earth jurisprudence and are derived from the laws of nature. They can be seen as one sub-set of the broader Earth jurisprudence philosophy; as the “legal thread” that weaves together with so many other aspects of governance — including economics, institutional structures, and politics — to give expression to Earth jurisprudence. In his book, Cullinan discusses law, regulation and governance, acknowledging that all these concepts need to be made ‘wild’ and Earth centred.15

Many of the key elements of Earth jurisprudence and eco-centrism have long been debated in environmental philosophy and human ecology, and eco-centrism in the law has been explored by many writers, including Christopher Stone,16 Roderick Nash,17 and Klaus Bosselmann.18 The work of Berry and Cullinan builds on this body of work, but I would argue that it also offers something new. In addition to being a critical theory stimulating a growing body of literature,19 Earth jurisprudence and Wild Law are increasingly becoming practical and constructive tools as well. This is reflected in the growing international movement of people and organisations who are advocating for Earth-centred law and governance, and who are explicitly building their movements on the work of Berry and Cullinan.20 It has also been demonstrated by inspiring, real-world examples of social change and Earth-centred law and governance, such as the Ecuadorian Constitution,21 Bolivia’s 2010 legislation,22 and the 150 local level Rights of Nature ordinances that now exist in the United States.23

One of the many elements making up the complex web of Earth jurisprudence is the legal recognition of the rights of nature.24 Many advocates of Earth jurisprudence have argued that the Earth community and all the beings that constitute it have “rights”, including the right to exist, the right to habitat or a place to be, and the right to participate in the evolution of the Earth community.25 Berry argued that ‘nature’s rights should be the central issue in any … discussion of the legal context of our society’.26 From this view, nature deserves to be valued for its own inherent worth. This contrasts with the dominant legal system, which grants rights only to humans and selected social constructs such as corporations and treats plants, animals, and entire ecosystems, as human property. Granting rights to nature is a radical rethinking of the role of our anthropocentric legal system, and yet the idea appears to be taking hold in many jurisdictions. The legislation mentioned above, in Ecuador, Bolivia, and the United States, move Earth-centred ideas from merely a theory, to a practical framework for action. It should be noted that a rights-based approach is not just about conferring rights on nature. It is a means of giving legal recognition to nature’s inherent worth by recognising what is already there. In operational terms, it is a means of redressing the balance between humans and nature. It empowers those in the human community who are ‘anxious to restore balance when they find themselves in conflict with powers and authorities who prefer to see nature as solely a resource to be exploited for human ends’.27

III THE GLOBAL ALLIANCE AND ITS CREATION OF THE RIGHTS OF NATURE TRIBUNAL

The Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature (‘the Global Alliance’)28 was formed in 2010, by an international group of Earth lawyers and Earth advocates who attended the World People’s Congress on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth, held in Cochabamba Bolivia. The lawyers who comprise the founding members of the Alliance played an important role in drafting the UDRME,29 and agreed to create a permanent network of people committed to implementing Earth Jurisprudence and the Rights of Nature. The Global Alliance is made up of around 70 organisations around the world, including groups from the “global north”, “global south”, and First People’s nations. AELA, Australia’s only organisation created to advocate for Earth jurisprudence and rights of nature, is a founding member of the Global Alliance.30

The Global Alliance hosted a summit for its members in January 2014, in Otavalo, Ecuador. More than 70 people from around the world met to discuss Earth jurisprudence and rights of nature initiatives and collaborate on further projects. In the lead up to the Summit, a team of Ecuadorian lawyers suggested that they hold a “citizens tribunal” while the Global Alliance meeting was being held. The Tribunal was created as a response to the perception by local Ecuadorians that the Correa administration was not implementing the Rights of Nature provisions in the Ecuadorian Constitution and was instead allowing the rights of nature to be violated. The Tribunal was created to hear both Ecuadorian and international cases, and it was decided that each meeting of the Tribunal would have two functions: to admit new cases for later consideration and to make final decisions and recommendations about cases admitted at earlier hearings. The first cases presented to the Tribunal were: British Petroleum’s pollution of the Gulf of Mexico; Hydrofracking in the USA; the Chevron/Texaco case in Ecuador; the case of the failed attempt to protect Yasuni-ITT, Ecuador; the Condor Mine, Mirador, Ecuador; and the Great Barrier Reef Case, presented by the Australian Earth Laws Alliance, Australia. Two further issues were presented for advisory opinions — the danger to life on Earth presented by genetically modified organisms (‘GMO’) and a special case presented on behalf of ‘defenders of nature’ who had recently been persecuted by the Ecuadorian government.31

During his opening remarks, Prosecutor for the Earth, Ramiro Avila declared that, ‘[w]e the people assume the authority to conduct an International Tribunal for the Rights of Nature. We will investigate cases of environmental destruction, which violate the Rights of Nature’.32 The international panel of judges sitting on the Tribunal included lawyers and ethics experts from around the world, and these are listed on the Global Alliance website.33

IV THE GREAT BARRIER REEF CASE

The Great Barrier Reef case was presented to the Tribunal by AELA. As the National Convenor of AELA, I submitted written and oral evidence on behalf of the Reef, drawing on scientific reports and information collated in Australia.34 The case argued that the Rights of Mother Earth are being violated, because the Great Barrier Reef’s very existence is under threat. The Reef is under threat from a combination of land based marine pollution, the existing and proposed expansion of coal port development in human settlements adjacent to the reef, and the escalating carbon pollution in the atmosphere, which is causing devastating climate change. The case highlighted that in 2012, UNESCO issued, for the first time, a warning to the Australian Government that the Reef was under threat and its World Heritage Listing may be downgraded to ‘at risk’.35

The UDRME states that Mother Earth and all beings of which she is composed have inherent rights, including the right to ‘regenerate its bio-capacity and to continue its vital cycles and processes, free from human disruptions’.36 It also states that ‘[t]he rights of each being are limited by the rights of other beings and any conflict between their rights must be resolved in a way that maintains the integrity, balance, and health of Mother Earth’.37 The Great Barrier Reef case argued that human activities are disrupting the Great Barrier Reefs’ ability to continue its vital cycles and processes, and argued that the Queensland and Australian Governments must: (i) be held to account for allowing the volume of industrial development that is now occurring on the Queensland coast and threatening the Reef; and (ii) set limits on human developments and ensure the Great Barrier Reef can continue its vital cycles and processes and continue its evolutionary journey.

At the end of the factual basis for the case, I used the innovative framework of the Tribunal to do something that would never be admitted in a western style court of law. I spoke on behalf of the Great Barrier Reef, as a member of the Earth community and a “legal entity”. I acknowledged the Traditional Custodians of the land and sea country that comprises what is now called the Great Barrier Reef, and acknowledged that I was not a Traditional Custodian, just a concerned member of the Australian human community. My statement included the following:

You can quantify my length and my size and the fact that I can be seen from outer space, but in my world I am a home. I am a colourful, vibrant network of connected coral villages, made by the collective effort of millions of coral polyps over millions of years. Free swimming coral babies float about until they find a place to settle, and they normally settle on the comforting skeletons of their ancestors. They have made walls and mounds and hills of coral that, in turn, are the home for others in our community: algae, sponges, starfish, molluscs, sea snakes, fish. These coral homes weave in and out and around hundreds of islands. The islands themselves are homes to crabs, who scuttle in the shallows, turtles who entrust their eggs to the warm, sandy beaches. Many of these beaches are disappearing for them. Without the Reef, there is no home, no cosy place to play, nowhere to hide from predators, nowhere to lay their eggs. If the Reef dissolves and disappears, so will all of the thousands of species of life that call the Reef home. If the Reef disappears, there is nowhere else for these communities of life. If the world above the Reef grows hotter, the world of the Reef will change. And the world is surely changing.

For thousands of years people would visit us at the Reef: pop in and out with their little boats, take some fish with great respect, then go home. But now the ships have gotten bigger. And there are many more of them. We watch the coastline with fear when there are great rains, as the rivers fill up with sediment, destroyed and disturbed by the people on the land, and the garbage and litter and junk comes out of the rivers to our Reef.

In closing, I said:

So in conclusion, how might the Reef feel? I would imagine the Reef feels the same way that people who love and care about the Reef feel. We are frightened. We are frightened that something precious and irreplaceable and ancient will die.

I choked up a little as I finished my presentation. It was deeply disturbing to imagine the world from the point of view of the Great Barrier Reef. As I returned to my seat, I worried that my closing remarks had been too “emotional”. But I needn’t have worried. Afterwards, several Indigenous leaders from Ecuador and North America quietly thanked me for speaking for nature. One was crying when she hugged me, and thanked me for ‘speaking the truth about what we are doing to Mother Earth’. Two women from the USA came to me with tears in their eyes, because I had ‘touched their hearts’ with my words. Other members of the audience later thanked me, for speaking for nature.

Whether I spoke accurately for the reef or not is debatable. But I felt that it was important to speak on behalf of life itself — not just to present scientific data and legal justifications. That I had the freedom to do so, speaks to one of the greatest potential strengths of the Tribunal — the ability to use a formal structure, present evidence about environmental harm, argue for new legal frameworks, but also to then break free of the usual “fact based” focus of western style law to speak from the heart, as a member of the Earth community, concerned about other members of the Earth community. This is an important aspect of the Tribunal for the Rights of Nature, because a worldview based on Earth jurisprudence and the recognition of the intrinsic rights of nature to exist, thrive, and evolve is about much more than rational scientific knowledge and legal process. It is about recognising the miraculous existence of the complex web of life on this planet and nurturing it so that life can continue to evolve into the future.

At the end of the hearing, each of the judges on the Tribunal was responsible for making declarative statements about the cases, and determining if the cases should be admitted to the Tribunal for further investigation. Cormac Cullinan was appointed as the Tribunal member for the Barrier Reef Case. His decision is worth setting out in full:

I find a credible case that the Rights of Nature are being violated on the Great Barrier Reef (‘GBR’) and will continue to be violated. The claim has been brought on behalf of the Reef itself, which is a community of many beings — their right to exist will be adversely affected. The plaintiff has also identified the Queensland and Australian National Governments, as well as the corporations engaging in coal mining and export. We also heard that UNESCO recently released a report stating that the GBR may have to be added to the list of ecosystems at risk. There is a present and very real threat to the GBR.

Have the Rights of Nature been violated in this case? General principles must be looked at first. The Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth establishes a general duty of every human being as responsible for respecting and living in harmony with Mother Earth, and every human being and every public and private institution has a duty to act in accordance with the rights and obligations recognised in the Declaration. There are also specific duties mentioned in the Universal Declaration that are relevant to this case. For example, it states that States and public and private institutions must establish precautionary and restrictive measures to prevent human activities from causing species extinction, the destruction of ecosystems or the destruction of ecological cycles. In this case, it is clear that some of the institutions, like the federal and state governments are under a duty to prevent the destruction of the GBR. There is also a duty to ensure that the pursuit of human wellbeing contributes to the wellbeing of Mother Earth now and in the future. The evidence presented suggests that the exploitation of these coral reserves will not contribute to the present and future wellbeing of Mother Earth.

There was also specific evidence relating to the violation of the following rights: the right to be free from contamination, pollution, and toxic or radioactive waste; the right to integral health, for example the health of the Reef being affected, as well as the health of fish and other beings; and the right of every being to wellbeing. We also heard evidence of the destruction of the Reef ecosystem, which is potentially a violation of the right to continue the vital cycles and processes of the Reef, free from human disruptions. And if we consider what would possibly justify any such infringement of the rights, the evidence that this may be justified was not presented. In fact, on the contrary, this damage to the Reef is being driven by an increase in coal exports that will contribute directly to the acceleration of climate change and further disruption of ecosystems.

So not only is there evidence presented of the failure to comply with the duties in the Universal Declaration and violation of certain rights laid down in the Declaration, but this case also raises important issues for consideration, which have the potential of global significance. For example, the Tribunal should consider questions such as the following: if the amount of greenhouse gases in the air is already so great that it is causing significant climate change, is any significant increase in the rate of production of hydrocarbons, such as coal mining, automatically a violation of the Rights of Nature and of Mother Earth? This is a question that this particular case provides us and is important for consideration. Accordingly, my conclusion is that there is a case to answer and that this case must be admitted for consideration by the permanent Tribunal.38

The case was accepted by the Tribunal and it announced it would make its findings and recommendations known at the next Tribunal Hearing, in December 2014.

V REGIONAL CHAMBER: AUSTRALIA’S FIRST RIGHTS OF NATURE TRIBUNAL HEARS EVIDENCE ABOUT THE GREAT BARRIER REEF

The next stage in the Great Barrier Reef case was the convening of Australia’s first Rights of Nature Tribunal in Brisbane, Queensland on 15 October 2014. The Tribunal was technically a Regional Chamber of the International Tribunal and its objective was to hear evidence from local witnesses for the Great Barrier Reef case.

The role of the Regional Chamber is the same as the International Tribunal — to examine and make formal observations about ethics and violations of nature’s rights with regard to issues that have remained outside the consideration of formal government institutions. In addition to examining the plight of the Great Barrier Reef, the Regional Chamber also placed on trial current legal and economic systems that legalise and monetise the destruction of nature.

The Tribunal Judges were leading Australian scientists, Emeritus Professor Ian Lowe AM and Professor Brendan Mackey; ethicist and Adjunct Professor Noel Preston; Indigenous community leader from South East Queensland, Sam Watson and youth representative, Janelle Fabio. The prosecutor for the Earth was Benedict Coyne and the defence counsel, representing the Australian and Queensland Government, was Abraham O’Neill.

The Regional Chamber heard evidence from prosecution witnesses Joanne Bragg, Chief Executive Officer of the Environmental Defenders Office Queensland (‘EDO Qld’); Sean Ryan, Principal Solicitor of the EDO Qld; Dr Glen Holmes, marine biologist and reef expert from the University of Queensland; Brynn Matthews, Chairperson of the Environmental Defenders Office Far North Queensland (‘EDOFNQ’) and Cairns resident. I was the final witness for the Tribunal and I spoke for the Reef, reiterating the statement I made at the Tribunal Hearing in Quito in January.

After deliberation, the Regional Chamber made eight main recommendations that were forwarded to the International Tribunal. These can be summarised under four main headings. Firstly, the Regional Chamber found that the evidence is sufficient to support the argument that the Great Barrier Reef’s rights to exist, thrive and evolve have been and are being violated. In particular, three articles of the UDRME were being violated: the right to exist,39 the right to regenerate its bio-capacity and to continue its vital cycles and processes free from human disruptions,40 and the right to maintain its identity and integrity as a distinct, self-regulating and interrelated being.41

Secondly, the Judges of the Regional Chamber noted the evidence, which stated that intervention at this stage, that could ensure the cessation of further industrial development along the coastline adjacent to the reef, would support the restoration of the Great Barrier Reef and such action is the responsibility of the State and Federal government. Thirdly, while appropriate enforcement of existing environmental law in Australia would assist the health of the Reef, the Judges of the Regional Chamber stated that ‘it is clear that given the overwhelming impacts from the ongoing growth in current modes of production and consumption a new ethical and legal framing and an eco-centric ethic and legal system is needed such as that given legal expression in the Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth’.42 Finally, the Regional Chamber also recommended that Indigenous communities who are custodians of the land and sea country linked to the Great Barrier Reef need to be involved in a special Rights of Nature Tribunal during 2015 and this is currently being organised by AELA.

The findings and judgment from the Regional Chamber were included as part of the Great Barrier Reef Case which was heard in Lima, Peru in December 2014 in parallel with the UNFCCC COP 20 meeting. In its official findings, the Tribunal condemned the Australian and Queensland governments for permitting the rights of the Great Barrier Reef to be violated, demanded a range of actions be carried out that would reduce the human pressure on the Reef and petitioned the governments to comply with the recommendations by UNESCO.

VI WHAT DOES THE INTERNATIONAL RIGHTS OF NATURE TRIBUNAL OFFER THE GREAT BARRIER REEF AND EARTH JURISPRUDENCE?

As the western legal system generally, and Australian legal system in particular, does not recognise the rights of nature, what can the Tribunal offer jurisprudence, environmental activism, or the Great Barrier Reef?

One of the key reasons the Tribunal was created was to give a voice to the voiceless: to allow us to speak for nature and challenge the destructive practices that industrial society has normalised throughout the 20th Century. By offering an alternative, Earth-centred legal analysis, the Tribunal casts light on specific injustices inflicted on the Earth community, injustices that are currently legal and morally endorsed by nation states and vested interests. Further, by critiquing the foundations and impact of the current legal system, the Tribunal draws attention to the flawed and devastating outcome of our anthropocentric laws and growth-obsessed government policies.

While the Tribunal’s decisions are not part of international law or enforceable in any nation state’s legal system, it has been argued that decisions like those from the Tribunal will have ‘performative significance as a forum in which an alternative “rights of nature” legal discourse can be articulated and developed’.43 Further, such alternative jurisprudence ‘compel us to interrogate existing legal principles, practices, and findings … through a wild law lens and can contribute to a paradigm shift in existing legal systems’.44

The potential for the Tribunal to contribute to a paradigm shift was particularly obvious during the Regional Chamber of the Rights of Nature Tribunal, held in Brisbane on 15 October 2014. The expert witnesses, and decisions by the Tribunal members, involved a fascinating mix of discussions about existing environmental laws and normative legal structures based on an Earth centred approach, recognising the rights of nature. This melding of conceptual analysis was extremely valuable, not least because the lawyers involved in giving evidence, the Tribunal members involved in giving their opinions, and the audience involved in interpreting and later sharing these ideas, were all engaged in an act of creative extrapolation: critiquing existing law in order to pull it apart, lay it bare, reframe it, and begin building something new. After the Tribunal in Brisbane, community members from Northern Queensland contacted AELA, expressing interest in developing campaigns to advocate for the Great Barrier Reef to be recognised as having its own legal rights. While this doesn’t offer immediate, increased protection for our beloved Reef, it is hoped that this will help the Great Barrier Reef by empowering environmental activists and lawyers with new concepts, a new vocabulary, and a vision for how the legal system should work to the Reef and all ecosystems on Earth.

VII CONCLUSIONS

In this article I have mapped out the origins, purpose, and ongoing activities of the International Tribunal for the Rights of Nature. The Tribunal offers a space for Earth lawyers to articulate and critique the legalised atrocities committed against the Earth community. By doing so, it offers a unique place where existing laws are brought together with normative frameworks that recognise the Rights of Nature. It can help us imagine a more just, compassionate, and effective legal system. It also provides concerned citizens with a new language for advocating for better environmental stewardship by our elected representatives. Finally, the Rights of Nature Tribunal offers a powerful alternative narrative to that offered by western legal systems regarding environmental destruction. By problematizing the destruction as morally unacceptable violations of the Rights of Nature, it has the potential to assist the movement toward Earth centred stewardship of our precious planet.

For a printable copy, visit: Maloney_Finally Being Heard_Griffith Journal of Law and Human Dignity 2015

*Michelle Maloney is the National Convenor of the Australian Earth Laws Alliance and is also currently working at the Center for Earth Jurisprudence, Barry University Law School, Florida USA. She can be contacted on convenor@earthlaws.org.au.

______________________________________

1 See also Australian Earth Law Alliance, Home (2014) www.earthlaws.org.au

2 Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, Universal Declaration of Rights of Mother Earth (2015)

3 See, eg, Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador 2008 (Ecuador) (‘Ecuadorian Constitution’) [Georgetown School of Foreign Service trans http://pdba.georgetown.edu/Constitutions/Ecuador/english08.html; Bolivia: Ley Marco de la Madre Tierra y Desarrollo Integral para Vivir Bien 2012 (Bolivia) http://www.lexivox.org/norms/BO-L-N300.xhtml

4 See, eg, World People’s Conference on Climate Change and the Rights of Mother Earth, Rights of Mother Earth: Proposal Universal Declaration of the Rights of Mother Earth, Word Press http://pwccc.wordpress.com/programa/

5 Linda Sheehan, ‘Nature’s rule of law through rights of waterways’ in Christina Voigt (ed), Rule of Law for Nature: New Dimensions and Ideas in Environmental Law (Cambridge University Press, 2013) 230.

6 Ibid.

7 See also Places You Love Alliance, Protecting Nature Laws, Places You Love http://www.placesyoulove.org/who-we-are/protecting-nature-laws/. For example, in 2013 in Australia, the Federal Government proposed to devolve its responsibilities under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (‘EPBC’) Act to the States. This was considered a significant threat to the operation of environmental laws in Australia and triggered the creation of the largest alliance of Australian environmental organisations who have been actively working to protect against the proposed reduction of Australia’s environmental laws.

8 See also Australian Earth Law Alliance, above n 1.

9 Thomas Berry, The Great Work: Our Way Into the Future (Bell Tower, 1999); Thomas Berry, ‘Rights of the Earth: We Need a New Legal Framework Which Recognises the Rights of All Living Beings’ on Resurgence & Ecologist Magazine (September/October 2002) http://www.resurgence.org/magazine/issue214-challenge-at-johannesburg.html.

10 Ibid.

11 Brian Swimme and Thomas Berry, The Universe Story: From the Primordial Flaring Forth to the Ecozoic Era — A Celebration of the Unfolding of the Cosmos (Harper Collins, 1992).

12 Berry, The Great Work: Our Way Into the Future, above n 9, 125.

13 Ibid.

14 Cormac Cullinan, Wild Law: A Manifesto for Earth Justice (Green Books, 2003).

15 Ibid.

16 Christopher Stone, ‘Should Trees Have Standing? Law, Morality and the Environment’ (1972) 45 Southern California Law Review 450.

17 Roderick Frazier Nash, The Rights of Nature: A History of Environmental Ethics (University of Wisconsin Press, 1989).

18 Klaus Bosselmann, ‘Governing the Global Commons: The Ecocentric Approach to International Environmental Law’ in M Prieur and S Doumbé-Billé (eds), Droit de l´environment et développement durable (Presses Universitaires de Limoges, 1994).

19 Cullinan, above n 14; Peter Burdon (ed), Exploring Wild Law: The Philosophy of Earth Jurisprudence (Wakefield Press, 2011); Michelle Maloney and Peter Burdon (eds), Wild Law — In Practice (Routledge, 2014).

20 See also Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, Founding Organisations and Members (2015) garn.org/founding-organizations.

21 Ecuadorian Constitution.

22 Bolivia: Ley Marco de la Madre Tierra y Desarrollo Integral para Vivir Bien 2012 (Bolivia) http://www.lexivox.org/norms/BO-L-N300.xhtml.

23 See also CELDF, Community Environment Legal Defence Fund www.celdf.org/.

24 Berry, The Great Work: Our Way Into the Future, above n 9; Berry, Rights of the Earth: We Need a New Legal Framework Which Recognises the Rights of All Living Beings, above n 9; Cullinan, above n 14; Stone, above n 16; Cormac Cullinan, ‘If Nature Had Rights, What Would We Have to Give Up?’ on Orion Magazine (January 2008) https://orionmagazine.org/article/if-nature-had-rights/ .

25 Berry, The Great Work: Our Way Into the Future, above n 9.

26 Ibid 80.

27 Lynda Warren, Begonia Filgueira and Ian Mason, Wild Law: Is there any evidence of Earth jurisprudence in existing law and practice? (Gaia Foundation, 2009).

28 See also Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, Home (2015) garn.org

29 Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, above n 2.

30 See, eg, Australian Earth Law Alliance, above n 1.

31 See also Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, International Rights of Nature Tribunal – Quito (2015) garn.org/rights-of-nature-tribunal/

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

34 See also Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, Cormac Cullinan Judges Ruling on Great Barrier Reef Case (2015) garn.org/cormac-cullinan-great-barrier-reef-case. A copy of the written material was presented to the Tribunal in January 2014.

35 Ibid.

36 Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, above n 2, art 2(1)(c).

37 Ibid art 1(7).

38 Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, above n 34.

39 Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, above n 2, art 2(1)(a).

40 Ibid art 2(1)(c).

41 Ibid art 2(1)(d).

42 Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, Great Barrier Reef Case – Lima (2015) garn.org/great-barrier-reef-case-lima

43 Nicole Rogers and Michelle Maloney, ‘The Australian Wild Law Judgment Project’ (2014) 39(3) Alternative Law Journal 172.

44 Ibid.

REFERENCE LIST

A Articles/Books/Reports

Berry, Thomas, The Great Work: Our Way Into the Future (Bell Tower, 1999)

Bosselmann, Klaus, ‘Governing the Global Commons: The Ecocentric Approach to International Environmental Law’ in M Prieur and S Doumbé-Billé (eds), Droit de l´environment et développement durable (Presses Universitaires dw Limoges, 1994)

Burdon, Peter (ed), Exploring Wild Law: The Philosophy of Earth Jurisprudence (Wakefield Press, 2011)

Cormac Cullinan, ‘If Nature Had Rights, What Would We Have to Give Up?’ on Orion Magazine (January 2008) https://orionmagazine.org/article/if-nature-had-rights

Cullinan, Cormac, Wild Law: A Manifesto for Earth Justice (Green Books, 2003)

Maloney, Michelle and Peter Burdon (eds), Wild Law — in Practice (Routledge, 2014)

Nash, Roderick Frazier, The Rights of Nature: A History of Environmental Ethics (University of Wisconsin Press, 1989)

Rogers, Nicole and Michelle Maloney, ‘The Australian Wild Law Judgment Project’ (2014) 39(3) Alternative Law Journal 172

Sheehan, Linda, ‘Nature’s rule of law through rights of waterways’ in Christina Voigt (ed), Rule of Law for Nature: New Dimensions and Ideas in Environmental Law (Cambridge University Press, 2013)

Stone, Christopher, ‘Should Trees Have Standing? Law, Morality and the Environment’ (1972) 45 Southern California Law Review

Swimme, Brian and Thomas Berry, The Universe Story: From the Primordial Flaring Forth to the Ecozoic Era — A Celebration of the Unfolding of the Cosmos (Harper Collins, 1992)

Warren, Lynda, Filgueira, Begonia and Mason, Ian, Wild Law: Is there any evidence of Earth jurisprudence in existing law and practice? (Gaia Foundation, 2009)

B Legislation

Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador 2008 (Ecuador) [Georgetown School of Foreign Service trans http://pdba.georgetown.edu/Constitutions/Ecuador/english08.html

Bolivia: Ley Marco de la Madre Tierra y Desarrollo Integral para Vivir Bien 2012 (Bolivia) http://www.lexivox.org/norms/BO-L-N300.xhtml

C Other

Australian Earth Law Alliance, Home (2014) Australian Earth Law Alliance www.earthlaws.org.au

Berry, Thomas, ‘Rights of the Earth: We Need a New Legal Framework Which Recognises the Rights of All Living Beings’ on Resurgence & Ecologist Magazine (September/October 2002) http://www.resurgence.org/magazine/issue214-challenge-at-johannesburg.html

CELDF, Community Environment Legal Defence Fund (2015) Community Environment Legal Defence Fund www.celdf.org/

Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, Cormac Cullinan Judges Ruling on Great Barrier Reef Case (2015) garn.org/cormac-cullinan-great-barrier-reef-case

Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, Founding Organisations and Members (2015) garn.org/founding-organizations

Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, Great Barrier Reef Case – Lima (2015) garn.org

Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, Home (2015) garn.org

Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, International Rights of Nature Tribunal – Quito (2015) garn.org/rights-of-nature-tribunal

Global Alliance for the Rights of Nature, Universal Declaration of Rights of Mother Earth (2015) garn.org/universal-declaration